Mastering minimalism: Roger Deakins

Who is the most iconic filmmaker alive? Well, many will say Roger Deakins, and we won't argue with them.

Roger Deakins in his 70s was nominated for "Oscar" 15 times out of which he triumphed only twice - for "Blade Runner 2049" and "1917".

According to the cinematographer himself, every director with whom he has ever worked is different, they create unique screen worlds which don't always have to conform to the rules of reality, to be naturalistic. The key is to create a seamless experience for the audience to believe in. Today our blog is dedicated to the legendary Roger Deakins: we want to pay proper tribute to the master, as well as break down the main methods of the master who helped shape the visual style of iconic pictures.

Disclaimer: our blog has no academic purpose behind it, because we are viewers just like you. Filmustage does not aim to educate, but to gather a close-knit film community around us. We can be wrong about certain statements - and that is fine. We are open to discussion and criticism. The main thing is to love cinema and talk about it.

Each director has a different idea of how the script will look on the screen. That's why being able to create the image of your film in pre-production is extremely important. Visualise how you see all the elements in your script with Filmustage's Visual Reference board.

Art by @nadi_bulochka

Roger Deakins' style: the 4 main techniques

Playing on the contrast

In his youth, Deakins started with painting and graphic design, and then moved on to photography. And it became his bridge to the cinema - first documentary, and then art. Therefore, Deakins' style is still based on the basic techniques of working with color and light, as well as the contrasts they generate.

Roger Deakins never seeks to surprise viewers - on the contrary, he recreates naturalistic worlds. That's why he often works in natural light - in "Prisoners", "Sicario" and "No Country for Old Men", for example.

Deakins likes the so-called "regime time," which is what twilight is called in cinematography. In such conditions, it is easiest to show a pronounced color contrast and draw the viewer's attention to important details. Sometimes this timing creates iconic images, like in the famous scene from "Sicario".

It's a technique that not only focuses attention on details, but also introduces the viewer to the character, showing the strength of his strokes, his body energy and his movement style, which is faster and easier to understand than any exposition. The dark silhouettes in this case also serve as a great accent for the viewer, whose attention should not be scattered in the action scenes. Sometimes you even get a kind of "shadow theater" during which the viewer looks more closely at the details - as in the scene from "Skyfall" with the fight in the background of a jellyfish.

Deakins' desire to keep things as simple as possible, using natural and practical lighting, also stems from his early career. In "1917", as well as in "Sicario" or "The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford", the cinematographer tries to use "real" light as much as possible. Deakins waits for the necessary conditions, monitoring the weather forecast in real time. Such patience is rewarded with impressive scenes, like the climax of "1917" shot entirely in sunlight.

Sometimes, however, you can't achieve proper conditions without artificial lighting. For certain scenes, Deakins has to cheat and create lighting that imitates natural light. For example, for a scene from "1917" a five-tier wall with two thousand bulbs was built, so that there was exactly enough light in the wide shot. In this way Deakins imitated fire. The light from the rocket is also a simulation, created by manipulating sparks and LEDs.

In this way, Deakins uses contrasts to drown out unnecessary details, but to highlight the essentials of the scene. It's exactly the same principle that the English cinematographer uses in his portraits: he often darkens one half of the hero's face, leaving the other half bright. And the light is set in such a way that the face is reversed by the light in the background - a double contrast is created.

Simple but tasteful

Deakins doesn't look for exotic locations, but poetizes the everyday. Perhaps that's why he worked so successfully with the Coen Brothers.

Most of the pictures he shoots are realistic and chamberlike, while blockbusters and sci-fi are more of an exception. The cinematographer always tries to make the world of the film as natural as possible, so that the viewer does not have to think about how it was shot. The main difficulties in Deakins' work are not technical, but conceptual.

Deakins draws specific conditions in his imagination and tries to embody them as accurately as possible on the screen - so the weather is very important to him. For example, the shooting of "Prisoners" was originally decided in dark colors, and the cinematographer followed this idea till the end. The difficulty was that the film had too many street scenes.

Weather conditions help Deakins make the shot intense, whether it's an unusual sunrise over the wasteland or heavy precipitation in a cityscape. Sometimes iconic shots are made possible by "happy moments," what professionals call "unpredictable gifts of nature", like sunlight appearing in the windows.

But even without them, and without artificially created rain, Deakins always knows how to fill the space of the frame. For example, with color, as in "Blade Runner 2049". Or with the abundance of insignificant details in the background, as in any of the Coen brothers movies - just remember at least the episode with the gas station attendant from "No Country for Old Men", where the background, on the one hand, represents an empty space, and on the other, is hung with straps, as if symbolizing a gallows.

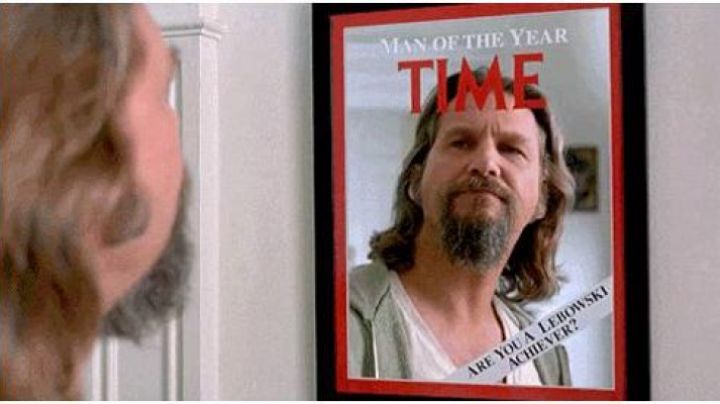

The same simple techniques help Deakins to avoid banality in everyday scenes. He often uses framing (most of the single episodes with 'K' from "Blade Runner 2049"), guide lines (as in this shot from "Barton Fink") and other elements of visual geometry, like mirror reflections.

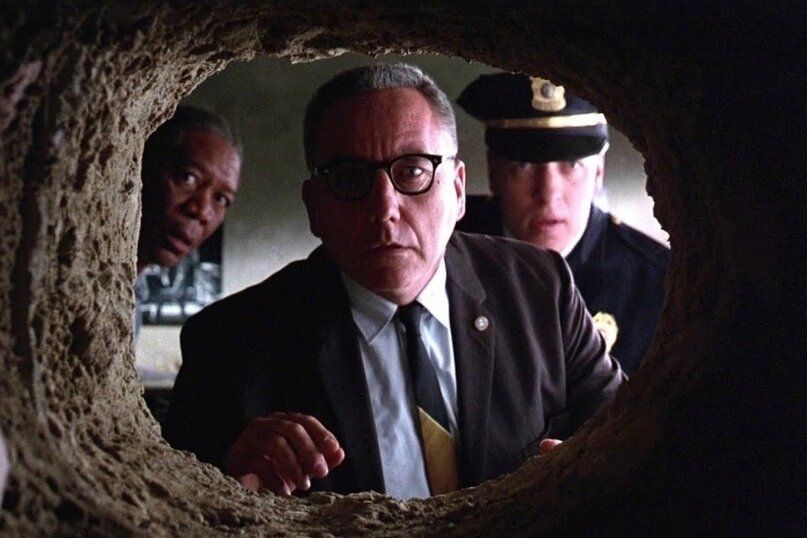

"The Shawshank Redemption" is particularly beautiful in its simplicity. The color in this film always accurately conveys the mood of the characters, and the unusual angles clearly show the emotional tone of the scene. For example, in the episode when the warden tears down the poster - the camera focuses on the eye and slowly moves away from it, showing the surprise of the characters.

An even more striking example is the iconic shot in the rain, which has become a symbol of freedom. The camera is at the bottom for a long time, hiding the surroundings, and then slowly rises, filling the frame with free space.

Minimalism in the work is also a purely technical matter: Roger Deakins prefers to use a single camera, and only three lighting sources - with some of them located in the frame itself. The practical lighting adds an extra ambience: it could be the lamps in the diner that divide the frame into parts, or the neon lighting of the streets of the future.

Good preparation is the key to success

Starting his career in documentary filmmaking on British television, Deakins had to sail around the world on a yacht. He spent 9 months in extreme conditions, not only for life, but also for the production of the film: the filmmaker had to save a lot of film, because there was nowhere to get a new one. This experience taught the cameraman to think everything through in advance and take his time to prepare for filming. Since then, it has been one of Deakins' main credo.

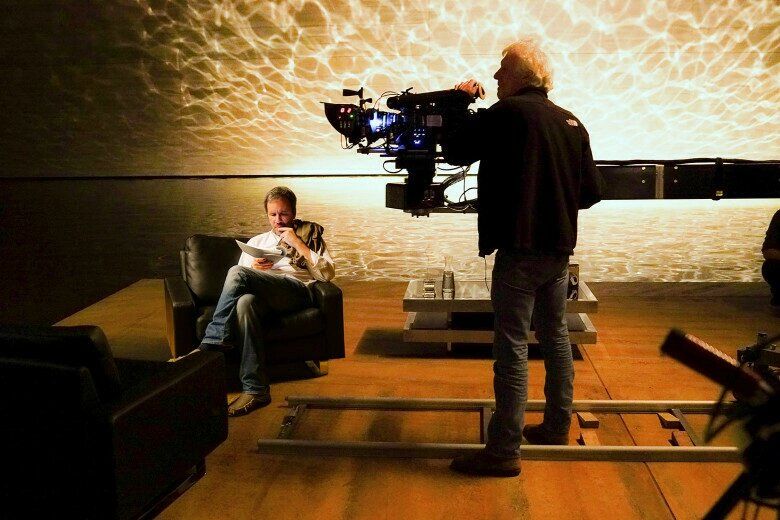

The record-breaking preparatory period came in the pre-production of "Blade Runner 2049" - it lasted exactly a year. Director Denis Villeneuve entrusted Deakins with all the key decisions, from the choice of lenses to the color design of scenes. Therefore the cameraman was actively involved in all stages of preparation: from the creation of storyboards to 3D-visualization.

Deakins often says in interviews that he doesn't have a single style and that he is always guided by the needs of the project. Deakins approached the filming of "1917" in the same way.

Director Sam Mendes decided to shoot the film using one shot technique. Reading the notes in the script, Deakins did not believe for a long time that Mendes really intended to do it that way. When the director explained the plan, the cinematographer agreed and began the preparatory period, which took nearly 9 months.

The entire filming process, including timings, camera passes and in-frame editing, was thought out even before the sets were built. Deakins could be considered a full-fledged collaborator on every project he worked on. He is involved in the production from the first to the last days and in many ways determines the visual style of the film.

The story is at the center of it all

In many interviews, Deakins says that the most important thing for him is to tell the story. He makes any decisions only after a detailed conversation with the director about the underlying meaning of the scene. Deakins' goal is not to surprise the viewer with a beautiful shot, but to show a meaningful visual metaphor that moves the story forward and reveals new subtexts.

This approach is inspired by the films of his favorite directors, especially Andrei Tarkovsky ("Ivan's Childhood" which Deakins calls one of the most important films of his life). Of course, he is also inspired by the work of the cinematographers who shot these films.

Deakins' visual metaphors are simple and straightforward. In "A Beautiful Mind", he alludes to the film's central theme through reflections. The monumental abode of Wallace from "Blade Runner 2049" is turned into a temple by the cinematographer with a single light. The camera is static, but the light is constantly in motion: this is achieved by moving the light panels. And, for example, the story of "1917" is looped through a simple leitmotif - a yellow flower. Interestingly, the color yellow runs through the entire narrative in both "1917" and "Blade Runner 2049". Only in "1917" another important leitmotif was added - white cherry blossoms, which, thanks to the monologue of one of the characters, became a symbol of hope.

Deakins' camera always works to tell the story in an accessible way. His favorite method is to use a wide-angle lens to portrait the characters. In this way he shows the character's surroundings, which always tell his/her/their story.

The life of the sheriff in "No Country for Old Men" tells us from the first shots that he is tired and uncomfortable with the modern world. Pay attention to the things (old dishes and a lamp) and the background (typical old man's pale yellow colors and an old crooked tree in the window) - they seem to shout about the character's retrograde attitude.

And almost all the portraits of 'K' from "Blade Runner 2049" show his loneliness and detachment from other characters - on the contrary, there are a lot of empty spaces in his background. Deakins reveals his loneliness with the help of wide-angle optics, but already in long shots, where 'K' is almost always distant from the interlocutor.

The aesthetics of "Blade Runner 2049" are created with the wide-angle lens, framing and dense light. From the combination of these elements come the majestic close-ups that have become the film's calling card. But Deakins emphasizes that he himself never admires such shots because he tries to think of the whole story at once and how to put it all together.

The large-scale idea of "1917" is also driven by the simple idea of involving the viewer as much as possible in the world of the film and thus bringing back the memory of a war that many have forgotten.

The chaos of military battles is shown through long plans - the heroes in the story can not stop, as well as the camera accompanying them. Through continuous shots, the illusion is created that all the horror going on around them really knows no end. This is why filmmakers often resort to this technique in battle scenes, be it "Saving Private Ryan" or "Children of Men".

"1917" was a new challenge for Deakins. The cinematographer has always been fond of static shots, which allow the viewer to take a break from the action and think about the philosophy of the film. But in "1917" the situation was the opposite. The whole filming process is an endless relay race with running, jumping in the trenches, falling and taking off. This kind of dynamic has not been typical of Deakins before. But this is what makes him unique - while the filmmaker claims to have no style of his own, each of his films has an unparalleled style that no one else could replicate.

Afterword

Let's be honest: the list of pictures Deakins has worked on speaks for itself. No single nomination or award is likely to fully reflect the contribution that Roger Deakins has made to the world of cinematography. He is the man who can capture the most functional, but the most evocative shots in cinema. In a word, a genius. We at Filmustage admire his talent and look forward to seeing more of his films.

From Breakdown to Budget in Clicks

Save time, cut costs, and let Filmustage’s AI handle the heavy lifting — all in a single day.